Down the QUIC Rabbit Hole, It All Started With MAX_STREAMS

How a single line of code led to understanding QUIC's revolutionary approach to transport, from TCP's head-of-line blocking to independent streams and flow control.

A few nights ago, while poking around a QUIC client implementation, I stumbled upon a curious bit of code in Cloudflare's quiche repository:

// In quiche examples/client.rs

conn.set_max_streams_bidi(100)?;

conn.set_max_streams_uni(3)?;

At first glance, it looked harmless, just setting how many streams a client can open. But that line sent me spiraling down a rabbit hole about how QUIC manages data, concurrency, and flow control, and why it's such a fundamental leap beyond TCP.

What You'll Learn:

- How TCP's head-of-line blocking creates bottlenecks

- Why QUIC's independent streams solve this problem

- What

MAX_STREAMSdoes and why it matters - How stream IDs work and prevent collisions

- QUIC's two-layer flow control system

The TCP Legacy: A Single-Lane Highway

For decades, the Internet relied on TCP, a protocol that guarantees:

- Reliability — every byte arrives

- In-order delivery — bytes arrive exactly in sequence

That second feature, in-order delivery, sounds like a good thing… until it's not. Because if one packet goes missing, everything behind it must wait.

The Problem: Head-of-Line (HOL) Blocking

This is the networking equivalent of a traffic jam behind one stalled car. One lost packet blocks everything behind it, even if those packets arrived successfully.

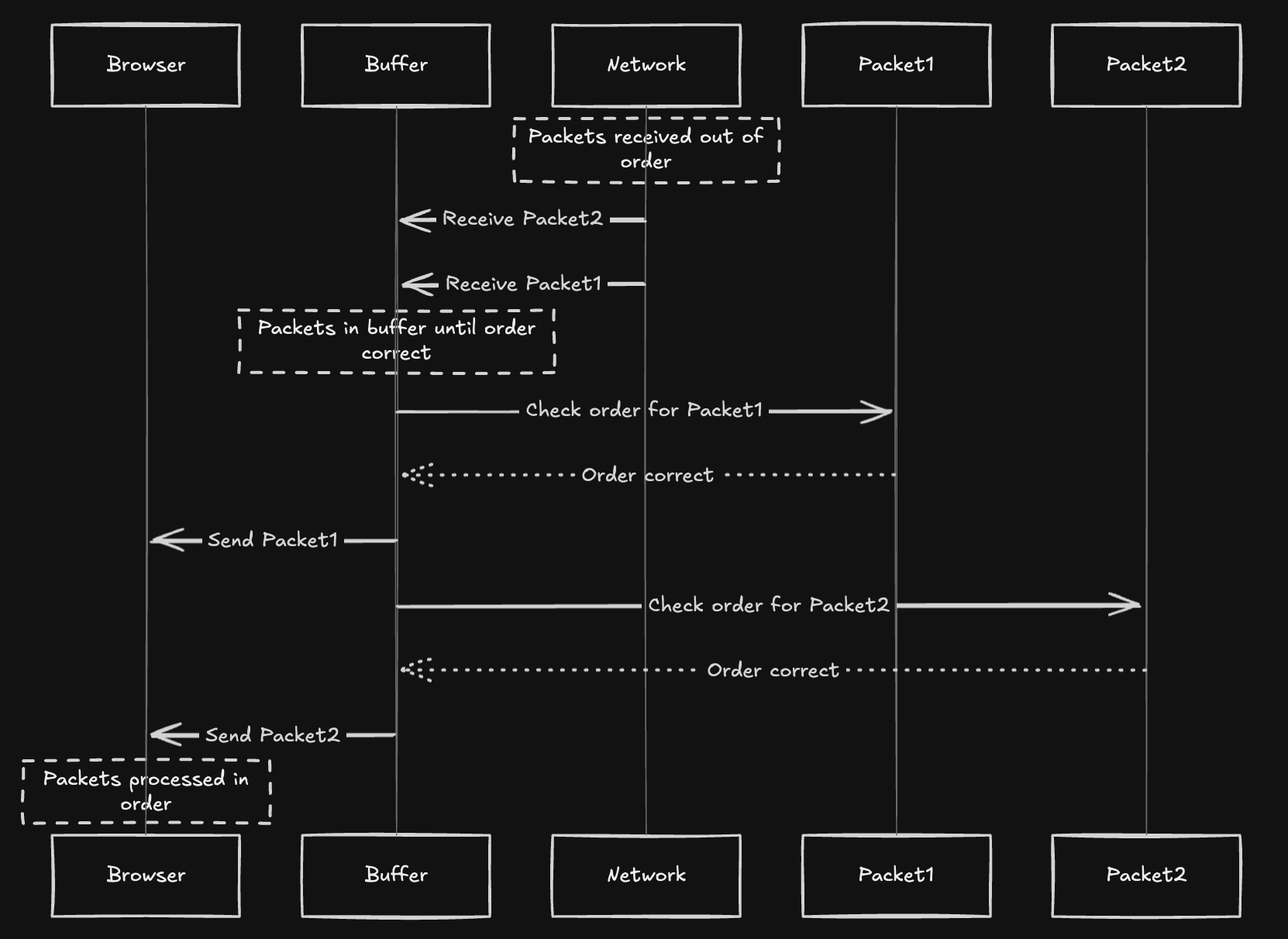

What's Happening Under the Hood

When packets arrive at the receiver, TCP uses a receive buffer to temporarily store them until they can be passed up to the application in the correct order.

Each packet has a sequence number:

Here's what happens next:

TCP's Sequential Delivery Process:

- Packets arrive out of order from the network. In this example, Packet2 arrives before Packet1.

- The buffer receives both packets and holds them temporarily.

- The buffer checks the order for Packet1. Since Packet1 is the next expected packet, the order is correct.

- The buffer sends Packet1 to the browser.

- The buffer checks the order for Packet2. Since Packet1 has been delivered, Packet2 is now the next expected packet, so the order is correct.

- The buffer sends Packet2 to the browser.

- The browser processes the packets in the correct order (Packet1, then Packet2).

This enforced order is why TCP stalls. It's not lazy, it's loyal to sequence integrity.

Why It Gets Worse with HTTP/2

HTTP/2 multiplexes multiple resources (HTML, CSS, JS, images) over one TCP connection. So if one TCP segment is missing, every HTTP stream waits for that retransmission.

The HTTP/2 Bottleneck

Even if your image data (packets #3–#5) is fine, it won't reach the browser until the lost CSS packet (#2) is back. That's how one tiny packet drop can ripple across an entire webpage.

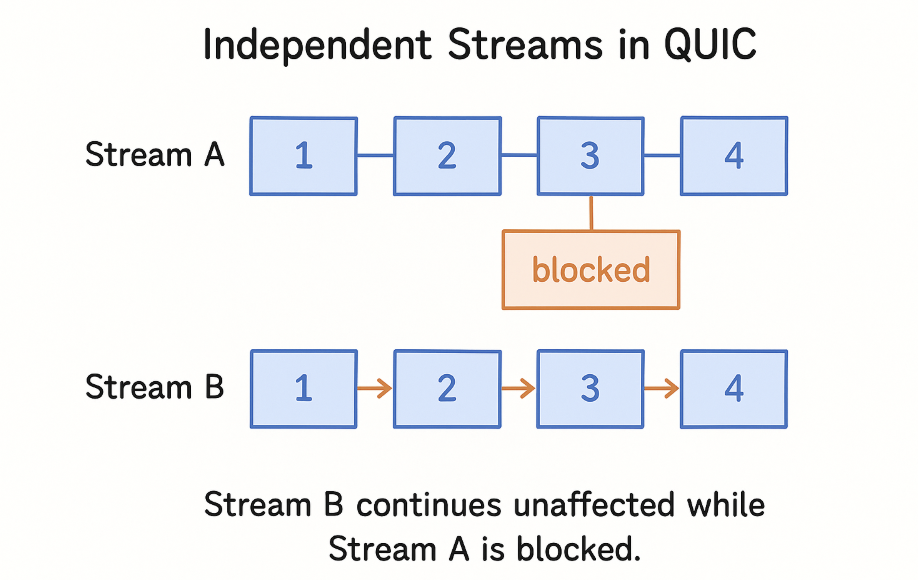

QUIC's Elegant Fix: A Multi-Lane Highway

QUIC, built on UDP, reimagines transport. Instead of one global stream, it introduces multiple independent streams, each with its own byte order, reliability, and flow control.

Think of it like multi-lane traffic: if one lane (stream) stalls, the others keep flowing.

HTTP/3 maps each HTTP request/response pair to a separate QUIC stream. So if /style.css gets delayed, /index.html and /image.jpg keep downloading smoothly.

Key Benefits:

- No head-of-line blocking between different resources

- Each stream has independent ordering and reliability

- Lost packets only affect their specific stream

Enter MAX_STREAMS: The Concurrency Gatekeeper

Back to that code I found:

conn.set_max_streams_bidi(100)?;

conn.set_max_streams_uni(3)?;

These lines define how many concurrent streams the peer can open at once. It's controlled via a frame called MAX_STREAMS, which is part of QUIC's flow control system.

In essence: "You can open up to N streams right now. Once some close, I'll let you open more."

This prevents one side from flooding the other with thousands of streams and exhausting memory.

For example, a server might advertise:

MAX_STREAMS(bidirectional) = 100MAX_STREAMS(unidirectional) = 3

What This Means:

The client can open:

- 100 bidirectional streams (request/response pairs)

- 3 unidirectional streams (control messages)

...all at the same time!

Stream IDs: How QUIC Identifies Streams

QUIC uses 62-bit stream IDs, encoding both the initiator and stream type:

| Initiator | Type | Stream IDs |

|---|---|---|

| Client | Bidirectional | 0, 4, 8, 12, … |

| Server | Bidirectional | 1, 5, 9, 13, … |

| Client | Unidirectional | 2, 6, 10, 14, … |

| Server | Unidirectional | 3, 7, 11, 15, … |

Why This Design?

These IDs make stream ownership clear and ensure no collisions. The last two bits encode who created the stream and what type it is.

Streams in Action: Real-World Multiplexing

When your browser fetches multiple assets, HTTP/3 simply opens new streams:

| Resource | Stream ID (example) |

|---|---|

/index.html | 0 |

/style.css | 4 |

/image.jpg | 8 |

Each stream carries one request/response pair. When packets arrive, QUIC knows exactly which stream (and thus which resource) they belong to.

No guessing, no blocking.

Flow Control: Two Layers of Protection

QUIC applies flow control in two scopes:

Two-Layer Flow Control:

- Per-stream — limits data in each individual stream buffer

- Per-connection — caps total buffered data across all streams

Together, they prevent any single stream from dominating the connection.

The "Aha" Moment: Why This Matters

That one config line…

conn.set_max_streams_bidi(100)?;

…isn't just a parameter. It represents a boundary of concurrency, the handshake between safety and speed.

The Fundamental Shift:

| TCP | QUIC |

|---|---|

| Forces order globally | Isolates ordering per stream |

| Blocks everyone for one lost packet | Lets other streams flow freely |

| Single-lane highway | Multi-lane highway |